Mental Health Holds and Civil Commitment

Published: June 2022

Download the 2022 Mental Health Holds and Civil Commitment print PDF (Full-Size Version)

Download the 2022 Mental Health Holds and Civil Commitment print PDF (Booklet Version)

Purpose of this Handbook

The purpose of this brochure is to provide general information about the rights of people with disabilities involved in the civil commitment process.

This information is provided as a public service and is not legal advice.

Your civil commitment attorney is the best resource for your questions and concerns, so please contact them to discuss your civil commitment.

Civil Commitment Overview

What is civil commitment?

Civil commitment is a legal process in which a judge decides whether a person should be required to accept mental health treatment.

The two most common reasons a judge orders someone to be civilly committed are:

they determine a person is a danger to themselves or others because they have a mental illness; or

they determine a person is unable to provide for their basic needs because they have a mental illness and the court believes a civil commitment is necessary to avoid serious physical harm in the near future.

A civil commitment is not a criminal conviction and will not go on a criminal record.

Can my guardian commit me?

Your guardian cannot civilly commit you. But if your guardian has been given authority to make placement decisions on your behalf, then they can admit you to a mental health facility, if a doctor from the facility agrees that admission is appropriate. You, or anyone else, may contact the court to object to the placement if you believe it is not in your best interest. You may also ask for an attorney to be appointed if you do not want to be hospitalized.

Can I be committed because I have a developmental disability?

It depends. Any two people may notify a court that a person in the county has an intellectual or developmental disability and needs to be committed for care, treatment, and training. This commitment may take place in the community or in a residential facility.

If this happens to you, there will be an investigation try to figure out whether you need to be committed or if there are other options. The investigation can take no more than thirty days. After the investigation, there is a hearing. You have a right to attend the hearing and have an attorney represent you. If the court determines that you should be civilly committed, the commitment can last for no longer than one year unless further papers are filed with the court.

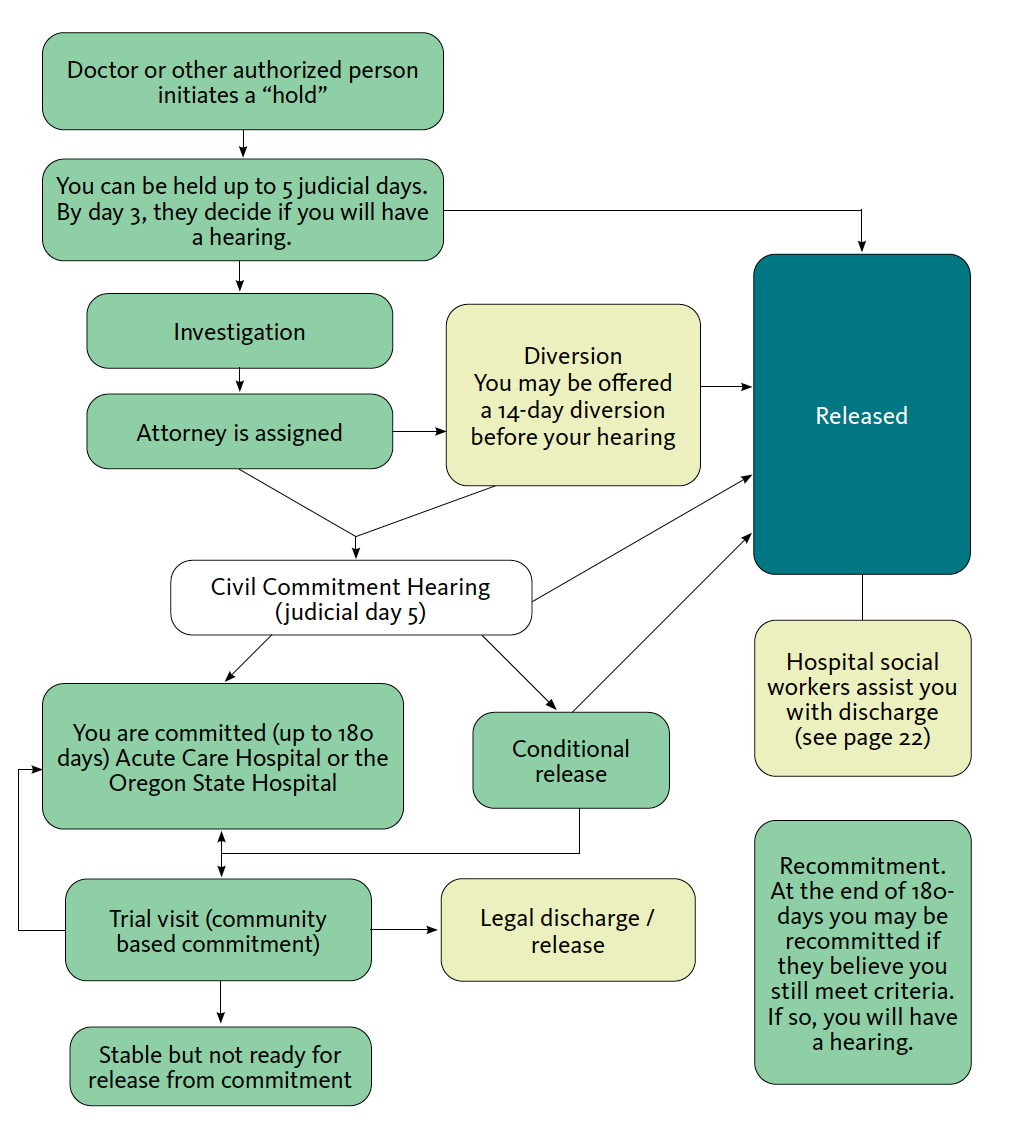

The Civil Commitment Process

This process begins if you have a mental health crisis and someone raises concerns about your safety or ability to meet your own needs.

Holds and the Pre-Commitment Process

What is a “hold”?

A hold—sometimes called a “pre-commitment hold”—is when a person is involuntarily held at a hospital or other mental health facility so they can receive mental health treatment.

You may only be placed on a hold if:

you are found to have a mental disorder; and

you are a danger to yourself or others.

Both of these conditions must be met. Not everyone who has a civil commitment hearing will be placed on a hold first. Some people remain in the community before their civil commitment hearing.

If you believe you should not be on a hold, you may request an attorney if you don’t already have one or talk to your attorney if you already have one.

Who can order a hold?

Holds are typically ordered by a doctor or a nurse practitioner at a hospital. In other cases, they may be ordered by a judge or a Community Mental Health Program (CMHP) director. Sometimes police officers will temporarily detain you and transport you to a hospital where authorized hospital staff will determine whether you should be placed on a hold.

How do I know if I am in the hospital voluntarily or have been placed on a hold?

You may ask staff at the hospital if you are there voluntarily or involuntarily. If they tell you that you are there voluntarily, you are free to leave. If they state that you are there involuntarily or on a hold, you may ask to see the “Notice of Mental Illness.” The Notice of Mental Illness should list the date that the hold started.

What type of facility can I be held at?

Generally, people on a hold are held at a hospital, such as a general hospital emergency room department, a psychiatric special emergency department, or an inpatient psychiatric hospital.

You must be held either at an approved hospital or a nonhospital that is able to provide adequate care and treatment. The facility should have trained staff and be able to meet your mental and physical health and safety needs.

If you have been charged with a crime or present a serious danger to hospital staff or property, you may be held in jail. Otherwise, you cannot be held in jail.

What if I am a voluntary patient and I want to leave?

Voluntary patients can discharge themselves from private, non-state facilities at any time. However, a doctor who believes you are dangerous to yourself or others may place a physician’s hold on you. This would require you to stay and be evaluated for civil commitment.

Generally, you would not be held voluntarily at a state facility. If you are, however, you can give them notice in writing that you want to be discharged, after which they can hold you for up to 72 hours.

How long can I be held before my civil commitment hearing?

No one can be held involuntarily longer than five judicial days unless a judge says so. You must be released at the end of five days during which the court is open and operating, unless:

you have a civil commitment hearing and a judge commits you;

you agree to voluntary treatment; or

you agree to diversion.

For example, if you are placed on a hold on Tuesday at 2:00 p.m., you must be released or have a hearing by the following Tuesday. This is five days from when your hold began, not including the weekend. If five judicial days pass and there is no court hearing, you are free to leave the hospital unless you have asked to postpone the hearing or have agreed to voluntary hospitalization or diversion.

Changing facilities does not affect this timeline.

Before the end of five judicial days, the investigator must assess you and recommend either a hearing or that you be released. In some cases, you may be released without meeting an investigator. If the facility has recommended you be committed, an investigator must meet with you and complete their investigation at least 24 hours before the hearing.

What rights do I have if I am on a pre-commitment hold?

While on a hold, you have many rights. Some of those rights are:

you have the right to an attorney, either a private attorney that you choose or an attorney appointed by the court if necessary;

you have the right to warning—both verbally and in writing—that doctor/patient confidentiality does not apply in civil commitment hearings;

you have the right to have your hearing postponed up to five judicial days. See below for more information on postponements;

you have the right to accept a fourteen-day diversion program only if agreed to by all sides. See page 12 for more information on diversion;

you have the right to remain silent with medical staff and commitment investigators regarding criminal activity;

you have the right to not speak to the investigator for your civil commitment. This may make it difficult for the investigator to make an accurate assessment about your commitment. See Commitment Investigation for more information about the investigation.

You have many other rights. See Rights Under Civil Commitment for an exhaustive list of rights that apply while on a hold and under civil commitment.

What is a postponement?

A postponement is a delay to the civil commitment hearing for up to five judicial days. You have the right to request a postponement of the hearing if you or your attorney need more time to prepare for the hearing. You should talk to your attorney about whether a postponement would be appropriate in your case.

Can I be involuntarily medicated?

Under some circumstances, you can be medicated without your consent. For example, you can be medicated without consent if:

there is an emergency; or

you are unable to consent and the treatment is medically necessary, appropriate, least restrictive, and in your best interest.

Before you can be involuntarily medicated, a doctor must show that a serious effort was made to obtain your consent or your guardian’s consent if you have one.

In addition, another psychiatrist must conduct an independent review. The second psychiatrist cannot provide primary or on-call care to you or to any facility employee. The facility administrator makes the final decision about approving or disapproving involuntary medication.

Note: The process for involuntary medication is different at the Oregon State Hospital. For more information on involuntary medication at the State Hospital, contact Disability Rights Oregon for additional publications, information, and referral.

Commitment Investigation

Who investigates civil commitment?

After a civil commitment petition is filed, an investigator from your County Mental Health Program investigates whether you need to be committed.

What does the investigator do?

The investigator interviews you as well as others who know you. The investigator also compiles information from your involuntary pre-commitment hold period. They may interview practitioners, nurses, or social workers and review records. The investigator’s goal is to determine whether they think you should be committed and to identify if there are alternatives to commitment. The investigator should base their decision on whether you meet the criteria for commitment (See Civil Commitment Criteria for more information about civil commitment criteria). The investigator then advises a judge whether to hold a court hearing.

What are the possible outcomes of the investigation?

The investigator will make a recommendation. They may recommend one of the following:

the case should be dismissed without a hearing and you should be released;

you should be offered a fourteen-day diversion program;

a civil commitment hearing should be held.

See What is a fourteen-day diversion program? for more information on diversion and see Civil Commitment Criteria and Hearing Process for information on the civil commitment hearing process.

Alternatives to Civil Commitment

Are there alternatives to civil commitment?

Yes. You may be given the option of receiving voluntary treatment in a hospital or “outpatient” treatment in the community. You may also be given the option of a fourteen-day diversion program.

What is community/outpatient treatment?

Community/outpatient treatment is treatment that takes place in your community or at a facility you go to for treatment but do not stay overnight or long-term. The hospital may talk to you about community-based or outpatient treatment. You have the right to participate in that treatment if it is offered to you.

What is a fourteen-day diversion program?

A fourteen-day diversion program can help people avoid civil commitment. Diversion is offered to some people while they are on a pre-commitment hold but before they have had their civil commitment hearing. The Community Mental Health Program (CMHP) Director is in charge of deciding whether they will offer diversion. If they decide you are eligible, they must offer diversion no later than three judicial days after you are put on the hold. When they offer diversion, it should include a statement of the treatment that you will receive. As soon as the court receives this offer, the court must notify your attorney or appoint an attorney if you do not have one.

You cannot be held for the fourteen-day treatment program without agreement of both you and your attorney.

If you agree to a fourteen-day diversion program, you can later change your mind and ask for a hearing. The hearing must be held within five judicial days of the request. If you refuse treatment, the CMHP Director can also ask for a hearing to be held within five judicial days.

You may be discharged at any time during the fourteen days, or may agree to voluntary treatment and ask for the case to be dismissed. If you are still being held after fourteen days and wish to leave, the facility cannot continue the program without a civil commitment hearing.

Civil Commitment Criteria and Hearing Process

What are the criteria for civil commitment?

You can be committed only if a judge finds by “clear and convincing evidence” that you have a mental disorder, and, because of that mental disorder:

you are dangerous to yourself or others; or

you are unable to provide for your own basic personal needs, such as health and safety.

Clear and convincing evidence means that the judge does not need absolute proof that the evidence presented in your case is accurate, only that it has a high chance of being accurate.

You may also be committed if you are found to meet all of the following criteria:

you have a diagnosis of a major mental disability such as chronic schizophrenia, a chronic major affective disorder, a chronic paranoid disorder, or another chronic psychotic disorder;

you have been committed and hospitalized twice in the last three years;

you show symptoms or behaviors substantially similar to those that led to a prior hospitalization; and

unless treated, it is medically probable you will continue to deteriorate and become a danger to yourself or others or be unable to provide for your own basic needs.

What is a civil commitment hearing?

At a civil commitment hearing, a judge determines whether you should be civilly committed. You, the “allegedly mentally ill person,” your attorney, the state’s attorney, and a mental health examiner are all present. Mental health examiners are doctors or other professionals certified by the state to make examinations at civil commitment proceedings.

Do I have the right to an attorney?

Yes. If you are unable to afford an attorney, the state may appoint an attorney to represent you. In some counties, public defenders’ offices have attorneys that specialize in civil commitment defense. You have the right to contact your attorney before your hearing. You can tell hospital staff, county mental health staff, or civil commitment investigators that you would like to talk to your attorney. See appendix for list for a list of offices that handle civil commitments.

Do I have a right to review records before my hearing?

The medical records put together by the court examiner’s investigation (see Commitment Investigation for more information about the investigation) should be made available to your attorney at least twenty-four hours before the hearing. You can ask your attorney to let you review the records as well.

Do I have a right to call witnesses to come to my hearing?

Yes. You have a right to call witnesses to testify at your civil commitment hearing. If you want someone to testify who is not willing to do so, your attorney can help you serve a subpoena that will require the person to come to your hearing. Using a subpoena to get a witness to your hearing may postpone the hearing.

Who participates in the civil commitment hearing?

A civil commitment is an open proceeding. Family and friends may attend. Both you and the state may call witnesses who can also attend. The investigator may also attend.

What happens in a civil commitment hearing?

During the hearing, your lawyer and the state’s representative will call witnesses to testify about your mental health and your behavior. You may also testify. The state’s attorney may question your witnesses and call other witnesses to testify about why you are mentally ill, dangerous, or unable to provide for your own basic needs.

Your attorney, the state’s attorney, the mental health examiner and the judge may ask the witnesses questions. Mental health examiners usually ask you questions and provide the judge with written opinions of your mental condition. Mental health examiners

are doctors or other professionals certified by the state to make examinations at civil commitment proceedings.

You, or your attorney, have a right to cross-examine witnesses, mental health examiners, and investigators. After all the testimony is finished, the attorneys make statements to the judge about why you should or should not be committed.

After hearing all the evidence, including reading the conclusions of the mental health examiners, the judge will make a decision about whether there is clear and convincing evidence that you should be committed.

What are the possible outcomes of a civil commitment hearing?

In the law, the term “mentally ill” means someone who has a mental disorder and is dangerous to themselves or others or is unable to care for their own basic needs. Simply having a mental disorder, whether diagnosed or not, is not sufficient on its own. If you are found by a judge to not be mentally ill, you should be released immediately and the case is dismissed.

If the judge decides you do have a mental disorder and are dangerous to yourself or others, unable to care for your own basic needs, or meet the expanded standard regarding prior hospitalizations, the judge will order that you be civilly committed.

If the judge finds you meet the standard for civil commitment, the judge may:

release you, if you are willing and able to participate in treatment on a voluntary basis and they believe you will probably do so;

conditionally release you into the custody of a friend or relative;

order you committed to the Oregon Health Authority for up to 180 days of treatment.

If you have been released, you are free to leave.

Can you appeal a civil commitment?

Yes. You can appeal a judge’s civil commitment decision. An appeal is a legal way to challenge the judge’s decision to commit you. A notice of appeal must be filed within 30 days of the commitment decision. If you wish to file an appeal, you should notify your attorney as soon as possible after the decision. Appeals usually take longer than 180 days to complete. This means if the commitment is reversed, you likely will not get out of the hospital any sooner, but some other rights may be preserved. See Rights Under Civil Commitment for rights affected by a civil commitment.

Rights Under Civil Commitment

How long can a civil commitment last?

A commitment can last no longer than 180 days. If the treating doctor or facility director believes you are no longer mentally ill, you must be released from the hospital or community setting even if 180 days have not passed. The hospital cannot keep you longer than 180 days unless you agree to stay or are re-committed by court order after being offered another hearing. See Post-Commitment for more information on recommitment.

It is rare, but if you are committed to assisted outpatient treatment instead of a hospital, your commitment can last up to twelve months.

Where are people under civil commitment placed?

People under civil commitment can be placed in several different settings including:

Oregon State Hospital;

Acute psychiatric care facilities;

Secure residential facilities; or

Community-based outpatient treatment.

Your placement is determined by the Community Mental Health Program Director of the county where you were committed.

What is outpatient commitment?

If you have been committed on an outpatient basis, you will be released under the supervision of the Community Mental Health Program (CMHP). The CMHP will release you so long as you agree to follow certain conditions. The conditions stay in effect for a period of time decided by the judge, up to 180 days.

What happens if I do not follow the conditions for outpatient commitment?

If you do not follow the conditions of your outpatient commitment, the CMHP Director may tell the court. The court may require another hearing to determine whether to change your placement or the conditions on your outpatient commitment. You have the same rights to an attorney as you do during your original civil commitment hearing.

What are my rights under a hold or civil commitment?

While civilly committed, you have many rights, but they may be limited to protect you and other people in the facility from serious harm. Some of your rights are listed below.

Your communication rights:

You have the right to communicate freely in person and by reasonable access to telephones.

You have the right to send and receive sealed mail.

You have the right to a reasonable supply of writing materials and stamps.

You have the right to visit with family members, friends, advocates, and legal and medical professionals.

Your due process rights:

You have the right to file grievances with the place you have been committed if you believe your rights are being violated. These rights include the right to have your grievances considered in a fair, timely, and impartial grievance procedure.

You have the right to representation by a lawyer whenever a substantial right may be affected.

You have the right to be informed at the start of services of your rights. You have the right to be informed about procedures for reporting abuse of your rights.

You have the right to be notified of any limitation of your right to: send or receive mail; privacy in resting, sleeping, dressing, bathing, personal hygiene, and toileting; access to fresh air; or disposal of your personal property. You also have the right to challenge these limitations.

Your treatment rights:

You have the right to a written treatment plan, kept current with your progress.

You have the right to choose from available services those which are appropriate and consistent with your treatment plan.

You have the right to treatment in the least restrictive environment appropriate for you.

You have the right to an individualized written service plan, services based on that plan, and periodic review and reassessment of service needs.

You have the right to keep playing a role in the planning of the services that you need in a way that is appropriate to your capabilities.

You have the right not to receive services without informed, voluntary written consent except in a medical emergency.

You have the right to be free from mechanical restraints, unless medically necessary. Any use of mechanical restraints must be documented.

You have the right to be free from potentially unusual or hazardous treatment procedures, including convulsive therapy, unless you have given express and informed consent or authorized the treatment. Under some circumstances this right may be denied, so involuntary treatment procedures are permitted.

Your civil rights:

You have the right to wear your own clothing.

You have the right to keep personal possessions.

You have the right to religious freedom.

You have the right to a private storage area with free access.

You have the right to decline to perform routine labor tasks, except those tasks that are essential for treatment.

You have the right to reasonable compensation for all work performed other than personal housekeeping duties.

You have the right to daily access to fresh air and the outdoors.

You have the right to reasonable privacy and security in resting, sleeping, dressing, bathing, personal hygiene, and toileting.

You have the right to exercise all civil rights in the same manner and with the same effect as one not admitted to the facility, including, but not limited to, the right to dispose of property, make purchases, enter contractual relationships, and vote, unless you have been found incompetent and have not been restored to legal capacity.

Your rights to be free from abuse and neglect:

You have the right to be free from abuse or neglect and to report any incident of abuse or neglect without being subject to retaliation.

You have the right to have access to and communicate privately with any public or private rights protection program or rights advocate, including Disability Rights Oregon.

You have the right to exercise all rights described in this section without any form of retaliation or punishment.

Who do I contact if I have concerns about how I am being treated at the hospital?

If you have concerns about the way you are being treated in the hospital, you may:

contact your civil commitment attorney. In many counties you can contact the public defender’s office. Your hold or civil commitment paperwork will say which county your commitment is filed in; See appendix for a list of offices that handle civil commitments.

contact the hospital’s patient relations department to discuss your concerns and file an internal complaint if necessary.

file a complaint with external oversight bodies and licensors. To do so, you may contact the hospital’s patient relations department for a full list of places to file complaints.

you may contact the Office of Training Investigation and Safety to file an abuse and neglect report:

Office of Training, Investigation and Safety 1-855-503-SAFE (7233)

You may also consider contacting a private attorney if you have concerns about medical malpractice:

Oregon State Bar Referral Service 800-452-7636

You may contact Disability Rights Oregon:

Disability Rights Oregon

503-243-2081

900 SW 5th Ave, Suite 1800

Portland, Oregon 97204

What are my rights at the Oregon State Hospital?

As a committed person, you have many of the rights you had outside of the hospital, such as the right to vote, to buy consumer items, and to marry. These rights can be limited in some cases, but never as punishment. For more information about your rights at the Oregon State Hospital, contact Disability Rights Oregon.

Who should I contact with questions about my civil commitment?

Once committed, you will have a contact person with the county. They are usually called “post-commitment monitor” or “exceptional needs care coordinator.” They would be a good person to ask questions about your care and placement. For specific questions about your legal situation, you should contact your attorney.

Release and Discharge

What is conditional release?

A conditional release means that you are released into the custody of a friend or relative, with certain conditions that you must follow. These conditions frequently include seeing a mental health worker and/or taking medication. Your friend or relative must tell the court if you do not follow your conditions for release. The conditions stay in effect for a period of time decided by the judge, up to 180 days.

What is a trial visit?

After being committed, you may be released into the community on a trial basis. A

trial visit comes with conditions, like taking medications or attending specific therapy sessions. You are still under commitment, but you are allowed to live in housing in the community, such as supportive housing or in your own home.

How can I get a trial visit or conditional release?

Ultimately the decision to allow a trial visit or conditional release is up to the judge. If you have a family member or friend who would be willing to assist in your care during a conditional release, you can talk to your attorney about bringing that person to the commitment hearing as a witness.

What happens if I do not follow the conditions for release or a trial visit?

You may face another hearing before a judge if you are on conditional release or on a trial visit and you do not follow the conditions. You have the right to an attorney and all the other rights granted to you for a civil commitment hearing. You may be held in custody before the hearing. If you are being held involuntarily before your hearing, your hearing must be within five judicial days of when the hold began.

If the judge finds you broke a condition, the judge can:

continue the placement with or without additional conditions; or

order you to be returned to state custody for involuntary care and treatment.

What should discharge planning look like?

Before you are discharged from mental health treatment, you should have the opportunity to plan for your discharge. That planning should cover whether you want other people to support you in discharge planning, a risk assessment, assessing your long-term care needs, coordinating with other care providers, and scheduling follow-up appointments within seven days of discharge. While you are in civil commitment, the Oregon Health Authority may also help you apply for public benefits programs that will support your discharge.

How do I get released or discharged from civil commitment?

When you are determined to no longer be a person with mental illness, you will be given the option of leaving the facility. The community mental health program director may also determine that voluntary treatment is in your best interest and release you from civil commitment. You would then have the option of continuing your treatment voluntarily.

You will be released after your commitment period (180 days) ends if the state does not seek recommitment. Recommitment is when the treatment staff believes you are not ready for release at the end of your commitment period. If the facility is seeking a recommitment, they would give you papers asking you to stay. You should receive any recommitment papers before your commitment is over.

Before you leave, the hospital should help you make a discharge plan and connect you to resources that you will need in the community once you are released.

Post-Commitment

Can I protest recommitment?

If you do not want to stay in the facility where you were committed, you must protest your recommitment by signing a protest form or by telling the hospital staff. You have fourteen days after receiving the papers to do this. You may be recommitted automatically for up to 180 days if you do not protest the recommitment.

If you protest recommitment, the hospital may not keep you in custody unless another hearing is held and the judge decides that you need to be recommitted.

For the purposes of this court hearing, you have the same rights as you did in your original commitment hearing:

You have the right to be represented by an attorney, who you can either hire yourself or have appointed by the court.

You have the right to have the hearing postponed to prepare or find an attorney.

You have the right to have a doctor or other qualified person who is not on the staff of the hospital or facility where you are held examine your mental condition and report the results to the judge.

You have the right to have your own examiner appointed at no expense.

Who pays for civil commitment?

The cost of treatment during a civil commitment may be billed to you. This bill is sent to your insurer if you have insurance. Generally, the Community Mental Health Program

for your county will pay any amount that remains after your insurance pays if you

are committed to a private hospital. If you were treated in a nonprofit hospital, the government may pay the bill if you do not have insurance or enough money to pay. If you were treated in a state institution, you have a right to a hearing about your ability to pay.

Can I sue if I’m falsely accused of being mentally ill and am civilly committed?

Anyone can file a lawsuit. But you can only win a suit for a false accusation of mental illness if there is bad faith, malice, or no probable cause existed to believe you could need commitment.

Can I request copies of my commitment record?

Yes. You may request a transcript of what the witnesses said in court at your civil commitment hearing. There is a fee for the transcript.

Is my commitment confidential?

Somewhat. Your treatment records are confidential unless you choose to share information with specific individuals. Your hearing is confidential. The fact that you were committed is also confidential.

The fact that you are or were committed to an institution may be available in some government databases. For example, the fact that you were committed may be disclosed to determine whether you may purchase a firearm. People who were interviewed during the investigation may also know that you were in civil commitment proceedings.

Can I choose to share confidential information with other people?

While committed, you may give permission to disclose confidential information. If a family member or any other person you choose requests this information, the facility where you are being held must disclose:

your diagnosis, the condition that your care provider has identified;

your prognosis, the expected outcome of planned treatment;

your prescribed medications, as well as side effects;

your progress;

information about the civil commitment process; and

where and when you may be visited.

If you are unable to give permission to disclose confidential information, the hospital will only reveal where you are, but cannot provide details about your condition or care. When you are committed to a hospital or treatment center as a patient, the staff will try to inform your closest family member or a chosen friend that you are committed at the facility. But that same family member or friend is not entitled to be told when you are released, moved, or seriously sick.

How are my legal rights affected by civil commitment?

Most legal rights are not affected by civil commitment. You retain most legal and civil rights, including the right to vote, unless a court has found you to be “incompetent,” but some specific rights can be limited as a result of civil commitment.

Firearms: A person who has been committed is forbidden from owning, buying, or possessing firearms. This restriction may be waived in some cases by following the required procedures to show that you do not pose a threat to yourself or the safety of the public. You may also be able to have your right to a firearm reinstated through a hearing process.

Immigration: A civil commitment may have immigration consequences. Talk to your attorney about how civil commitment could affect your immigration status.

Future Commitments: If you are committed twice within the past three years, it may be easier for you to be committed in the future.

Driving: A civil commitment may affect your ability to keep or get a driver’s license, specifically if you are found to be unable to exercise reasonable or ordinary control over a motor vehicle.

Appendix

Civil Commitment Attorney List

Clackamas County

Haub Wyatt Law

333 SW Taylor Street, Suite 300

Portland, OR 97204

503-782-4997

Law Office of Amanda J Marshall, LLC

294 Warner Milne Road

Oregon City, OR 97045

503-765-5748

Deschutes County

Deschutes Defenders

541-389-7723

Lane County

Public Defenders Service of Lane County, Inc.

541-484-2611

Marion County

Public Defender of Marion County, Inc

503-480-0521

Multnomah County

Metropolitan Public Defenders

503-225-9100

Washington County

Metropolitan Public Defenders

503-726-7900

Note: You should review your hold or civil commitment documents to determine in which county your civil commitment is filed. If your county is not listed in this appendix, you may ask the hospital staff to provide you with the phone number for the legal counsel contracted in your area.

Written by:

Lisa Rose Gagnon, Liz Reetz, Sarah Radcliffe

Copyright © June 2022 Disability Rights Oregon

900 SW 5th Ave, Suite 1800, Portland OR 97204

Voice: 503-243-2081 or 1-800-452-1694

Fax: 503-243-1738

E-mail: welcome@droregon.org

Website: www.droregon.org

Disability Rights Oregon is tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Contributions are tax-deductible and will be used to promote the rights of Oregonians with disabilities.

Portions of this Handbook may be reproduced without permission, provided that Disability Rights Oregon is appropriately credited.

NOTICE: This Handbook is not intended as a substitute for legal advice. Federal and state law can change at any time. You may wish to contact Disability Rights Oregon or consult with an attorney in your community if you require further information.

Disability Rights Oregon upholds the civil rights of people with disabilities to live, work, and engage in the community. The nonprofit works to transform systems, policies, and practices to give more people the opportunity to reach their full potential. For more than 40 years, the organization has served as Oregon’s Protection and Advocacy system.

This publication was made possible by funding support from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Administration for Community Living. These contents are solely the responsibility of the grantee and do not necessarily represent the official views of SAMHSA or ACL.

This information is available in alternate formats, including large print, Braille, audio, or electronic text file. Disability Rights Oregon and this publication are funded by federal and state grantors.