Special Education Guide: A Guide for Parents and Advocates

Although much of the law related to special education is still well explained by this guide, Disability Rights Oregon is currently revising it to reflect some important changes in federal and state laws. One of those changes is the passage of Senate Bill 819, which helps more Oregon children have access to full-day school. Read the FAQ >

Revision date: 2012

Download the 2012 Special Education Guide: A Guide for Parents and Advocates print PDF

Purpose of this Publication

This Guide was written to provide parents and advocates with accurate information and answers to questions about special education for children enrolled in Oregon’s public schools from Kindergarten to 21 years of age. The information in the Guide reflects recent changes to the major federal and state laws and regulations that affect special education. While we may make references to students enrolled in private school, parents of private school students should consult the Oregon Department of Education (ODE) website, which has a section on Special Education for Parentally Placed Private School Students: www.ode. state.or.us.

The purpose of this publication is to provide general information to individuals regarding their rights and protections under the law. This publication is not a substitute for legal advice. Federal and state law can change at any time. Contact Disability Rights Oregon or consult with an attorney in your community if you need additional help.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: An Introduction to Special Education

Chapter 2: The Identification of a Disability

Chapter 4: Eligibility for Special Education

Chapter 5: The Individualized Education Program (IEP)

Chapter 6: Placement in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE)

Chapter 7: Extended School Year (ESY) Services

Chapter 8: Physical Restraint and Seclusion

Chapter 10: Transition from Special Education to Adult Services

Chapter 12: Preparing for Meetings

Chapter 13: Resolving Disagreements

Chapter 14: Writing to School District Administrators

ODE Chart – Options for Complaints not within IDEA

Chapter 1: An Introduction to Special Education

What is the history of special education legislation?

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 92-142) was enacted in 1975. In 1990, it was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). PL 108-446, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et. seq.

The name change reflects the evolution of how society has come to view students with disabilities as individuals first, instead of as being defined entirely by their disability. IDEA ensures a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) to children with disabilities and defines most of your child’s rights to special education. Periodically, Congress updates the law and allocates money to special education and related services for eligible students with disabilities. The IDEA was revised in 1997, and most recently in 2004, and is now called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA). Although IDEIA changed some parts of IDEA, many people still call the new law IDEA or IDEA 2004. This edition will refer to IDEA 2004 and addresses all of the major changes to the earlier law.

What is FAPE?

FAPE is shorthand for the Free Appropriate Public Education that every child eligible for special education is entitled to receive. 20 U.S.C. § 1412(a)(1), 34 C.F.R. § 300.101, OAR 581- 015-2040.

It is the heart of special education and IDEA 2004. An Individualized Education Program or IEP is the basic tool that is used to provide FAPE. 20 U.S.C. § 1401(14), 34 C.F.R. § 300.22, OAR 581-015-2000(15).

Who is eligible?

Students are entitled to receive special education under IDEA 2004 if they have certain disabilities and are having problems learning or functioning successfully in school because of their disabilities. Signs of a disability may include:

• Slowness in learning

• Not seeing or hearing well

• Unexplained behavioral problems

• A serious illness

• Emotional problems

What disabilities are recognized under the IDEA 2004?

The following disabilities are recognized under the IDEA 2004:

• Autism

• Both deaf and blind

• Emotional disturbance

• Hearing impairment and deafness

• Intellectual disability

• Multiple disabilities

• Orthopedic impairment

• Other health impairments

• Specific Learning Disability (SLD)

• Speech or language impairment

• Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

• Visual impairment and blindness

20 U.S.C. § 1401(3), 34 C.F.R. § 300.8, OAR 581-015-2000(4)

What if my child doesn’t have one of these disabilities?

Some children may experience developmental delays in the areas of physical, cognitive, social-emotional, communication, or adaptive development. However, these children may not meet the standards to qualify for special education under one of the disability categories listed above. Students with disabilities such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADD/ADHD) or Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) may qualify for special education under Specific Learning Disability (SLD), emotional disturbance, or Other Health Impaired. These students are also protected from discrimination based on their disability under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). 29 U.S.C. § 794 (Section 504), 42 U.S.C. § 12101 (ADA).

See “What is the history of special education legislation?”.

What is Other Health Impaired?

A child may have a health condition that is not included in any of the listed categories, but which limits his or her strength and causes problems in learning. 34 C.F.R. § 300.8(c)(9), OAR 581-015-2165.

OTHER HEALTH-IMPAIRED CONDITIONS

• Asthma

• ADD/ADHD

• Diabetes

• Epilepsy

• Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS)

• Heart condition

• Hemophilia

• Tourette syndrome

What is Section 504?

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibits discrimination based on disability by programs receiving federal funds. School districts must comply with this law because they receive federal funds. As a result, they must provide the same access and opportunity to children with disabilities as those without disabilities.

STUDENTS THAT SECTION 504 PROTECTS

• Students with a physical or mental disability that substantially limits one or more major life activities – self-care, walking, seeing, speaking, hearing, breathing, learning, working.

• Students with a record of having a disability.

• Students that are thought to have a disability though they may not.

OAR 581-015-2390.

For example, a school district that provides a summer school program must allow students with disabilities to enroll in the program. For more information about Section 504 contact Disability Rights Oregon. See “Special Education Laws and Where to Find Them”

What is Early Intervention (EI)?

Early Intervention (EI) provides services for preschool children with disabilities from birth to three years of age.

Services for these children are met with an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) in a natural environment, as much as possible – this means an environment natural for a child without a disability, such as in the home and community settings.

The family’s needs, as it relates to the child’s disability, are considered unlike an Individualized Education Program (IEP) in which the family’s needs are not included.

What is Early Childhood Special Education (ECSE)?

Early Childhood Special Education (ECSE) provides services for preschool children with disabilities from three years of age until the age of eligibility for public school.

It is free, specially designed instruction meeting the unique needs of preschool children with disabilities. Services for these children are met in a preschool environment, and the family’s needs are still part of the IFSP.

Is there a general timetable for students under IDEA 2004?

0 – 3 YEARS OLD

• Early Intervention (EI).

• Services met through an IFSP.

• Natural environments, such as in the home.

3 – 5 YEARS OLD

• Early Childhood Special Education (ECSE).

• Services met through an IFSP.

• Pre-school environment.

5 – 16 YEARS OLD

• Services met through an Individualized Education Program (IEP). See “Chapter 5: The Individualized Education Program (IEP)”.

• Public school environment.

• Focus is on the individual student from Kindergarten age until age 21.

16 YEARS OLD

• Transition services must be in the IEP in effect when the student reaches age 16.

• Can begin when the student is younger if the IEP team agrees it is appropriate.

17 YEARS OLD

• School district gives notice to student regarding age of majority (18 years of age).

18 – 21 YEARS OLD

• Upon reaching the age of majority (18 years of age) the student makes all educational decisions.

• Exceptions: students who have an educational surrogate or legal guardian.

• School district is no longer responsible for educating the student once he/she finishes the school year of his/her 21st birthday. See “Chapter 10: Transition from Special Education to Adult Services”

Who makes decisions for a child?

Under IDEA 2004, an IEP team makes decisions about a child’s special education. See “Who attends the IEP meeting?”

In general, parents must be included in the team or any group or meeting that makes important educational decisions for children with disabilities, such as: • Evaluation of your child’s disability and eligibility for special education.

• IEP goals, objectives, related services such as assistive technology, and other supports your child may need.

• How to deal with discipline problems and whether the problems are related to your child’s disability.

• Educational placement.

• Transition services.

• Extended school year (ESY) services.

• Progress or lack of progress meeting annual goals.

For students age 16 through 21, both parents and students have roles in educational planning. Students aged 16 and older must be invited to the IEP meeting to participate in transition planning.

If transition planning begins before age 16, the student is still invited to participate. At 17, students must be informed of their rights under IDEA 2004 that may transfer to them. See “Chapter 10: Transition from Special Education to Adult Services”

For children who are wards of the court or have state guardians, the school district must appoint a surrogate parent to make educational decisions.

20 U.S.C. § 1415(b)(2), 34 C.F.R. § 300.519, OAR 581-015-2320.

The surrogate parent must be a person who knows about the child. That person can be a biological parent, a foster parent, or a Court-appointed Special Advocate (CASA). The surrogate parent has all of the legal rights of parents discussed in this Guide. A surrogate parent should not be an employee of the school district or any other agency that is involved in the education or care of the child.

Who is responsible?

The school district where your child lives is responsible for making sure that he or she receives FAPE. The school district may arrange for other private or public schools and agencies to provide services to your child, but must make sure that those services provide FAPE.

Who pays?

Students with disabilities are entitled to FAPE. The cost of implementing a child’s IEP cannot be passed on to parents or guardians. This includes the cost of related services and necessary assistive technology. 20 U.S.C. § 1412(a)(1), 34 C.F.R. § 300.17, OAR 581-015- 2040. However, with parental consent, school districts may bill a third party, such as a family’s private health insurance, to offset certain costs. 34 C.F.R. § 300.154(e), OAR 581-015- 2535. In order for school districts to bill a family’s private insurance, the parents must voluntarily consent to the third-party billing. School districts cannot force parents to consent if the billing would cause financial loss to the parents.

EXAMPLES OF FINANCIAL LOSS

• Decrease in available cap or lifetime coverage.

• Increase in insurance premiums.

• Termination of the insurance policy.

• Payment of expenses such as deductibles.

If parents refuse to allow the school district to file a claim against the family’s private insurance, the district is still responsible for providing the student with special education services. The school district cannot require parents to consent as a condition to providing special education services.

What are assistive technology (AT) and AT services?

Assistive technology (AT) is any kind of technology that makes it easier for someone with a disability to maintain or improve functional independence in activities like learning, working, walking, or speaking. AT includes services that help individuals choose and learn to use the equipment and devices best suited for them. 20 U.S.C. § 1401(1) and (2), 34 C.F.R. § 300.5 and 6, OAR 581-015-2000(2)&(3).

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY EXAMPLES

• Over-sized pens and word processors for writing.

• Augmentative communication devices for speaking.

• Magnifiers and enlarged print materials for reading.

• Clipboards and Velcro attachments for organizing materials.

If AT is necessary for your child, it will be identified as a special factor and be included on the IEP under Specially Designed Instruction, Related Services and/or Program Modifications, depending on the use or uses of the AT in your child’s education.

Like other parts of your child’s special education, the district must pay for AT, including the cost of repair, maintenance, and replacement of necessary AT devices and services. 34 C.F.R. § 300.105, OAR 581-015-2055. On occasion, the school may be required to purchase an AT device for your child’s use in your home, if it is necessary for your child to receive FAPE.

One exception to this requirement is that IDEA 2004 specifically excludes cochlear implants and/or their maintenance and programming as AT devices and related services that a district must provide to a special education student.

What is an appropriate education for my child?

You should try to get the best possible education for your child. Under federal and state law, however, school districts do not have a legal obligation to provide what is best for special education students – only what is “appropriate.”

Through many legal cases, and one pivotal case in the United States Supreme Court, the term appropriate has come to have a very specific meaning: a school district offers an appropriate education when it provides access to public education that is designed to Special Education Guide 11 give “meaningful benefit.” Hendrick Hudson District Board of Education v. Rowley, 458 U.S. 179 (1982). To be appropriate, services must be individualized to meet the unique needs of your child. Those needs are determined according to procedures spelled out in this Guide.

Chapter 2: The Identification of a Disability

What is Child Find?

Child Find is the obligation of every school district to identify, locate, and evaluate all children between the ages of birth and 21 who may need special education and related services. 20 U.S.C. § 1412(a)(3), 34 CFR § 300.111, OAR 581-015-2080. This includes children with disabilities who attend private schools, children with disabilities who have moved from grade to grade, and children with disabilities who are homeless or wards of the state.

Anyone – a parent, teacher, student, nurse, doctor, social worker – may request that a child be considered for special education.

The new law emphasizes that parents and others who request that a child be evaluated for special education put those requests in writing. See “Model Letters”

What do I do if I suspect my child has a disability?

If you suspect your child has a disability, request an evaluation in writing. Submit your request both to your child’s teacher and to the director of special education in your child’s school district. If your child is under five years of age, the school will refer you to your local Referral and Evaluation Agency.

Document the date you make the request for an evaluation, and follow-up with special education staff after a reasonable time if not contacted. See “Model Letter #2: Follow-up letter to a discussion with the school district”

Chapter 3: Evaluation

Children suspected of having disabilities must be tested prior to receiving special education. This testing is called an evaluation and its purpose is to:

• See if the child has a disability and is eligible for special education.

• Learn about the child’s abilities and disabilities.

• Determine appropriate special education and related services.

A full evaluation must be completed and an Individualized Education Program (IEP) developed before a student is placed in a special education program.

After the initial evaluation, the child must be re-evaluated every three years. However, the re-evaluation need not include any additional testing if the IEP team decides that no further data is necessary. A parent or teacher may request more frequent evaluations, if needed.

What is an initial evaluation?

The initial evaluation is the first time a child is being evaluated for special education. Parents have the right to give or refuse consent for this evaluation. After receiving parental consent, there is a 60-school day timeframe during which the initial evaluation must take place.

If a parent refuses consent, the school district may use mediation or due process hearing procedures to pursue an evaluation but is not required to do so. See “Chapter 13: Resolving Disagreements”

What must be included in an evaluation?

To determine a child’s eligibility and special needs, more than one test or evaluation must be given. The tests must not discriminate by race or culture and must be given in the child’s primary language and in the format most likely to yield accurate information about the child’s knowledge and capabilities academically, developmentally, and functionally, unless it is clearly impossible to do so. 20 U.S.C. § 1414, 34 C.F.R. § 300.301-300.311, OAR 581-015-2105 through 581-015-2115.

For example, if your child primarily communicates through sign language, the district must provide an evaluator who signs or a sign language interpreter. Children who primarily speak in a foreign language, such as Spanish, Russian, or Vietnamese must be tested in that language. The evaluation should include observations by all people who are familiar with the child, such as parents, teachers, and caregivers.

Your child must be evaluated in all areas related to any suspected disabilities.

EVALUATION AREAS

• Academic achievement

• Assistive technology

• Behavior

• Communication abilities

• Health status

• Hearing

• Intelligence

• Motor abilities

• Sensory needs

• Social and emotional status

• Vision

• Vocational aptitude

What is done with the evaluations?

The evaluators must prepare a written report with the results of the evaluation. Then the IEP team meets to review evaluation results and make decisions about a student’s eligibility for special education. The IEP team includes parents and someone who can explain evaluations and what the results mean for the child’s education. See “Chapter 5: The Individualized Education Program (IEP)”

How quickly should the evaluation be completed?

Evaluations must be done within 60 school days from the time the school received the request and your signed permission to evaluate. The school may be allowed more time if there are special circumstances or if a parent agrees to a longer period of time. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(a)(1)(C), 34 C.F.R. § 300.301(c)&(d), OAR 581-015-2110(5)(a)&(c).

What is re-evaluation?

Every three years, the school district must conduct what is called a “re-evaluation” of a student receiving special education services to determine if the student continues to Special Education Guide 15 be eligible. During the normal re-evaluation process, the IEP team should consider if the student has had recent relevant evaluations, or if more testing is needed to inform the team about what services are necessary to help educate the child. Parents can request an evaluation at any time if they have concerns that warrant more evaluations.

If the team decides no further evaluations are needed, the team then reviews the most recent evaluation data and eligibility criteria for special education, and determines if the student remains eligible for special education. There must be current evaluations showing that a student no longer requires special education services before the team can end eligibility. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(c)(5)(A), 34 C.F.R. § 300.305(e), OAR 581-015-2105(1)(d).

For example, consider a nine-year-old girl who needed assistance learning to read in the first grade because of a learning disability. If fourth grade evaluations show that she is now able to read and write at grade level, she can be found ineligible for special education services if there is no evidence that she is experiencing other school problems related to her disability.

FACTS TO REMEMBER ABOUT EVALUATIONS

• If parents request testing, the team cannot say no under most circumstances.

• Parents must give consent for a child to be re-evaluated unless the district can show that it tried several times to get parental consent without response.

The team can make any evaluation process more meaningful by giving a list of questions to the evaluators. Answers to focused questions can help the IEP team in planning for the child’s education.

EXAMPLES OF QUESTIONS FOR EVALUATORS

• How can my child become more independent with toileting?

• Would my child benefit from more community integration experiences?

• What vocational training would be appropriate for my child?

• How can my child learn to communicate choices and preferences?

• What is triggering my child’s angry outbursts, and what can be done to help my child develop more self-control?

• What supports are needed for my child to participate in a regular class setting?

What is an independent educational evaluation?

Parents who disagree with the results of school district evaluations have the right to request an independent educational evaluation at school district expense. 34 C.F.R. § 300.502, OAR 581-015-2305. If the school district disagrees with a request for an independent educational evaluation, the school district may request a due process hearing. If the Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) finds that the school district’s evaluation was appropriate, the school district will not have to pay for the independent evaluation.

Parents still have the right to an independent evaluation, but not at school district expense. The school district must consider any evaluation offered by the parents in making IEP and placement decisions. After a parent requests an independent evaluation, the school district must give the parent information about where an independent evaluation may be obtained, and a list of district criteria for independent evaluations. These criteria, including both the location and the qualifications of the examiner, must be the same as those the district uses when it evaluates other children.

Parents are not required to use an evaluator on the school district list, and the criteria used by the school district cannot be so restrictive that parents are prevented from getting a meaningful independent evaluation. In selecting an independent evaluator, parents should make sure the evaluator understands their concerns. Parents should prepare questions about the area of disagreement for the evaluator to answer. See the example questions listed above. The independent evaluator should be prepared to back conclusions and recommendations if called to participate in an IEP meeting or hearing.

What are my evaluation rights?

You have the overall right to consent or refuse consent for any evaluation or re-evaluation. If you fail to respond to a district’s request for consent, the district can conduct a re-evaluation without your consent, unless it involves an intelligence or personality test. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(a)(1)(D), 34 C.F.R. § 300.300, OAR 581-015-2090, OAR 581-015-2095(3).

You have the right to get written notice before any evaluation or re-evaluation of your child. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(b)(1), 34 C.F.R. § 300.304(a), OAR 581-015-2110(2). See “Chapter 11: Notice Rules”

You may request an independent evaluation if you disagree with an evaluation conducted by the school district, or if the district fails to conduct requested evaluations within a reasonable amount of time.

You have the right to receive a copy of the evaluation report and documentation of determination of eligibility. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(b)(4)(B), 34 C.F.R. § 300.306(a)(2), OAR 581-015- 2120(6).

You have the right to review and correct your child’s school records. School records include evaluation results. In most circumstances, schools must get your written consent before releasing your child’s records. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(b)(1), 34 C.F.R. § 300.501, OAR 581-015-2300. For more information about FERPA, See “Glossary”

You may request mediation, write a letter of complaint, or request a due process hearing to resolve any disagreement involving evaluations. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(b), (e), (f), 34 C.F.R. § 300.151-300.153 and 300.506-300.518, OAR 581-015-2030 and 581-015-2335 through 581-015- 2385. See “Chapter 13: Resolving Disagreements”

Chapter 4: Eligibility for Special Education

What is eligibility?

After a child’s initial evaluation is completed, the district must hold a meeting to decide whether or not the child is eligible for special education. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(b)(4) and (5), 34 C.F.R. § 300.306, OAR 581-015-2120.

That meeting must include a parent and relevant qualified professionals who can explain the evaluation results in the area of eligibility being considered, such as psychologists, behavioral experts, and speech and language professionals with expert understanding of the eligibility categories being considered.

Each disability category under the IDEA 2004 has different criteria that a child must meet in order to qualify for IDEA services. If you know what category your child is being evaluated for, we recommend that you review the eligibility criteria on the Oregon Department of Education (ODE) website before attending your child’s eligibility determination meeting. OAR 581-015-2130 through 581-015-2180.

What happens once my child is found eligible?

Once your child is found eligible, the district is required to provide special education services once you have signed consent for them to do so. However, if you refuse to sign consent to begin special education services the school district has no obligation or power to provide those services.

Can the district end my child’s eligibility?

Once your child has been found eligible for special education services, that eligibility cannot be ended or changed without an adequate evaluation and an eligibility determination meeting, which is a meeting to determine whether your child is still eligible. 20 USC § 1414(c)(5)(A), 34 CFR § 300.305(e), OAR 581-015-2105(1)(d), OAR 581-015-2120.

What if my child is not eligible?

Your child may qualify for services under a 504 plan even if not eligible for special education services under IDEA 2004. A 504 plan is an individualized plan required by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.

If your child has a qualifying disability, he or she may also qualify for services under a 504 plan while being evaluated for eligibility under IDEA 2004. This is important to remember if your child urgently needs help while the evaluation and eligibility processes are taking place. See “What is Section 504?”

Can I revoke my consent for special education services?

Yes, you can revoke your consent for special education services in writing at any time. However, if you do this, your child will no longer have the many rights and protections that the law provides to special education students. For instance, without those protections, your child could be suspended or expelled for behavior that is caused by a disability. Another option would be to ask for an IEP meeting to discuss why the services currently being provided are not working as you expected for your child. 34 C.F.R. § 300.300(b)(4), OAR 581-015-2090(4).

Chapter 5: The Individualized Education Program (IEP)

What is an IEP?

The Individualized Education Program (IEP) is the written plan for a child’s education services. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(d), 34 C.F.R. § 300.320, OAR 581-015-2200. The Oregon Department of Education (ODE) has guidelines and forms that have been revised to comply with IDEA 2004. There is an IEP form for students age 15 or younger, and one for students age 16 and older. Both guidelines and forms are posted on the ODE website. The ODE also accepts approved alternate forms.

The purpose of an IEP meeting is to develop an IEP with goals and objectives to address a child’s strengths and needs. These strengths and needs are determined by a combination of formal evaluations and informal observations by teachers, parents, and others. The IEP team must consider both the results of the initial or most recent evaluation and the concerns of the parents for enhancing their child’s education.

Every child with disabilities needing special education must have an initial IEP completed within 30 calendar days of eligibility. In accordance with the IEP, special education and related services must be made available to the child as soon as possible. In general, school districts must have an IEP in effect for each child with a disability at the beginning of each school year. The IEP must be reviewed and updated at least once each year.

Who attends the IEP meeting?

Parents or school district personnel may request an IEP meeting at any time. The following people must be at the IEP meeting and are considered the IEP team members:

One or both parents: Generally the most knowledgeable about the child. In cases where parents are unavailable or unwilling to be part of the team, a surrogate parent should fill this role.

Regular education teacher: Should be present if the student is or may need to be in a regular educational setting. The IDEA 2004 has reduced the requirement that a regular education teacher attend all IEP meetings, but only if there is a written agreement between the parent and district that the teacher’s presence is not necessary. See the ODE form Written Agreements between the Parent and District, posted on the ODE website.

Special education teacher or provider: Such as a resource room teacher, speech therapist, or occupational therapist.

School District representative: Qualified to provide or supervise special education, and knowledgeable about the general curriculum and availability of resources.

Person to interpret evaluation results: Qualified to interpret evaluation results and explain what the results mean in terms of teaching the student. This could be a person already on the team as described above.

Other individuals: By invitation only – with knowledge or special expertise regarding the student, when invited by the district or parents.

Student with the disability: For discussion of transition services and other participation as appropriate.

20 U.S.C. § 1414(d)(1)(B)-(d)(1)(D), 34 C.F.R. § 300.321, OAR 581-015-2210.

If parents have a hearing impairment or do not speak English, the school district must provide an interpreter at the meeting. 34 C.F.R. § 300.322(e), OAR 581-015-2190(3).

How are IEP meetings scheduled?

School districts must notify parents in writing sufficiently in advance so that one or both parents can attend the meeting, and schedule the meeting at a mutually agreed upon time and place. The written notice must also state the purpose, time, and place of the meeting, as well as who will attend. The school district may ask parents whom they intend to bring to the meeting.

Can the school conduct an IEP meeting without a parent?

School districts must make serious efforts to include parents at the IEP meeting and must be reasonable about scheduling and location. 34 C.F.R. § 300.322(d), OAR 581-015-2195(3).

Can members of the IEP team be excused?

Any team member may be excused if the parent and the school district agree in writing. However, that team member must provide a written report if his or her subject matter is discussed at the meeting.

Can the IEP be changed without a meeting?

IDEA 2004 now allows some changes to the IEP without a meeting, but only if the changes are in writing and by agreement of the district and parents. This does not change the requirement of an annual IEP review meeting. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(d)(3)(D), 34 C.F.R. § 300.324(a)(4), OAR 581-015-2225(2)(a).

What must be in my child’s IEP?

The list that follows contains some key pieces that must be in a legally adequate and useful IEP. A complete list is found at Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR) 581-015-2200 on the Oregon Secretary of State website. See also 20 U.S.C. § 1414(d)(1)(A), 34 C.F.R. § 300.320, OAR 581-015-2200 & 2205. See “Special Education Laws and Where to Find Them”

PRESENT LEVELS OF ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND FUNCTIONAL PERFORMANCE (PLAAFP)

Complete, accurate, and easy to understand description of your child’s abilities, strengths, and weaknesses. You should be sure to include concrete examples of your concerns, hopes, and your observations of your child’s strengths. This is a critically important part of a good IEP.

STATEMENT OF SPECIAL EDUCATION SERVICES, SUPPORTS, AND MODIFICATIONS THAT WILL BE PROVIDED TO YOUR CHILD

IDEA 2004 requires these items be chosen, if possible, on the basis of peer-reviewed research.

MEASURABLE ANNUAL GOALS

These goals should allow you to understand whether or not your child has made progress by the end of the school year.

SHORT-TERM GOALS OR BENCHMARKS

Required if your child is academically evaluated by alternate assessments rather than by statewide testing. This is no longer required in all IEPs, but is often a good idea.

STATEMENT OF YOUR CHILD’S TRANSITION SERVICE NEEDS AND A FULL-SCALE TRANSITION PLAN

Must be done no later than the IEP year in which your child turns 16, and earlier if appropriate.

STATEMENT ADDRESSING YOUR CHILD’S REMOVAL FROM THE REGULAR CLASSROOM

A statement of whether your child will need to be removed from the regular classroom and, if yes, for how long and for what reason.

STATEMENT ADDRESSING FIVE SPECIAL FACTORS

Addresses whether or not your child has an educational need in any of the following five areas: behavior, language, Braille instruction, communication, assistive technology. See “What other important requirements should I consider for my child’s IEP?”

What follows are examples of how certain specific sections of an IEP might be written. See the Oregon Department of Education (ODE) website for complete forms and guidelines.

Present levels of academic achievement and functional performance (PLAAFP)

Jason is able to add, subtract, and multiply whole numbers with 85% accuracy, but cannot accurately divide whole numbers without a calculator or times table.

He can comprehend and solve whole-number practical math problems when they are read to him and involve a single calculation, but becomes confused if they require multiple calculations.

He understands approximately 10 commonly used fractions (e.g. 1/2, 1/4, 3/4, 1/3, 2/3) and can solve one-step practical problems involving them, but he cannot perform calculations or estimate correct answers to practical problems that involve less commonly encountered fractions (e.g. 3/32, 5/19).

According to recent academic testing, Jason’s overall math skills have been measured at the 2.7 grade level. At the beginning of the school year, an achievement test measured his overall math skills at a grade level of 2.5.

Jason’s parents observed that one of Jason’s many strengths at home is accurately setting the table with enough tableware for a family of six.

Jason’s parents are concerned that the new skills he is reportedly learning have not added up to any measurable progress toward catching up with his fifth grade classmates in the last two years.

Short-term objective

In four of five opportunities, Jason will be able to correctly identify relevant units of measurement and use them to accurately estimate answers to practical math problems involving whole numbers and common fractions.

Goal

By the end of this school year, Jason will increase his measured overall level of academic performance in math from 2.7 to 3.7 as measured by a standardized achievement test.

What other important requirements should I consider for my child’s IEP?

If appropriate, the IEP must include a statement about the modifications and supports that teachers, instructional aides, and specialists may need to help your child make progress toward annual goals. For example, a teacher may need training on how to use your child’s communication device. This need for teacher training should be identified on the IEP.

The school must focus on your child’s involvement and progress in the general education curriculum. The general education curriculum is the accepted plan of instruction, courses, and activities that most children without disabilities receive. Make certain the IEP includes a statement about your child’s involvement in the general curriculum, and education with other children. For example, your child’s IEP will need to list any accommodations necessary to allow your child to participate in school plays, eat in the cafeteria, or complete homework assignments.

The IEP must either state that your child will participate in statewide assessments with individual appropriate accommodations or that your child will not participate in the assessments, and why. If your child will not participate in statewide assessments, the IEP team must decide on an alternate assessment, and explain why the particular alternate assessment is appropriate for your child. The location of services must be identified on the IEP so you know where your child will receive physical therapy services, reading instruction, or any other service provided by the district.

Under the IDEA 2004, there is a presumption that children with disabilities are to be educated in regular classes. If your child will not be educated in regular education classes and activities, the IEP must explain why your child will be educated separately. See “Chapter 6: Placement in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE)”

The IEP team must also consider and address five special factors in the IEP if your child has an educational need in any of the following areas:

Behavior: Students with behavior needs that affect learning.

Language: Students with limited English skills.

Braille instruction: Students who are blind or visually impaired.

Communication: For all students, and for students who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Assistive technology: For all students.

For additional information about how to write IEPs go to the Wrightslaw Special Education Law and Advocacy website, under Articles.

How can I learn about my child’s progress?

As a parent of a child with disabilities, you must be regularly informed of your child’s progress. How often this occurs must be stated on the IEP. The school district is obligated to inform you at least as often as it informs parents of children without disabilities. The IEP must be reviewed at minimum once a year, and needs to be revised, as appropriate, to deal with any lack of expected progress, results of any re-evaluation, information you provide about your child, your child’s anticipated needs, and other matters.

How can I be sure my child’s teachers will follow the IEP?

The IDEA 2004 requires that your child’s IEP be accessible to teachers, specialists, aides, and any provider responsible for implementing your child’s IEP. Each teacher or provider must be informed of his or her role in carrying out the IEP and of the individualized accommodations, modifications, and supports identified on your child’s IEP. Teachers must make a good faith effort to help your child achieve the goals and objectives listed on the IEP. 34 C.F.R. § 300.323(d), OAR 581-015-2220(3).

What are my IEP rights?

You have the right to:

Written notice any time the district proposes to review or revise your child’s IEP. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(c)(1), 34 C.F.R. § 300.503(a)(1), OAR 581-015-2310.

Written notice any time the district refuses to make a change you requested to the IEP. See “Chapter 11: Notice Rules”

Request an IEP meeting at any time.

Be present and participate in all IEP meetings concerning your child.

Invite others to the IEP meeting. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(d)(1)(B), 34 C.F.R. § 300.321, OAR 581- 015-2210.

Receive a copy of the IEP. 34 C.F.R. § 300.322(f), OAR 581-015-2195(5).

Have any part of the IEP explained to you. 34 C.F.R. § 300.322(e), OAR 581-015-2190(3).

Ask for additional IEP meetings, request mediation, write a letter of complaint, or request a due process hearing to resolve any disputes involving the IEP. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(b), (e), (f), 34 C.F.R. § 300.151-300.153 and 300.506-300.518, OAR 581-015-2030 and 581-015-2335 through 581-015-2385. See “Chapter 13: Resolving Disagreements”

Chapter 6: Placement in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE)

What is an educational placement?

An educational placement is the package of services and the setting needed to educate a child according to the IEP. It is not just a physical location. After the IEP team develops IEP goals and objectives, they determine the setting, or placement, in which the student can work toward these goals. 20 U.S.C. § 1412(a)(5), 34 C.F.R. § 300.114-300.117, OAR 581-015- 2240.

For example, a child’s placement may be a self-contained classroom for children with emotional disturbance that offers daily opportunity to interact with students without disabilities. If more than one classroom in the district can provide everything that the IEP calls for, a change from one of these classrooms to another would not be a change of placement. This means that the district could legally make this kind of change without an IEP meeting.

The decision about what sort of placement is needed, on the other hand, must be made by the IEP team and include parents after the IEP is created. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(e), 34 C.F.R. § 300.327, OAR 581-015-2250(1)(a).

According to the law, a change of placement without the necessary IEP meeting has occurred if a child is excluded from the IEP designated placement for more than 10 consecutive days (or in a series of removals that show a pattern) because of disciplinary actions such as suspensions.

How is placement decided?

The placement decision must be made by a group of people that includes someone with knowledge about the child and the meaning of evaluation results, and someone familiar with placement options. Parents must be included in this group. The placement decision is based on test results, teacher recommendations, and the student’s needs as dictated by the IEP. The placement must be one where all of the IEP goals and objectives can be addressed. 34 C.F.R. § 300.116, OAR 581-015-2250. The continuum of placement options is the scope of placements where an IEP can be implemented, and ranges from less to more restrictive.

CONTINUUM OF PLACEMENT OPTIONS

A regular classroom.

A regular classroom with modifications and/or supplemental aids and services.

A resource room for special education instruction with instruction in a regular classroom.

A classroom for children with disabilities located in a regular school (self-contained classroom).

Day or residential special schools, where many or all students may have disabilities.

A home, hospital, or institution-based program.

The district must ensure that this continuum is available to students in their district. 34 C.F.R. § 300.327, OAR 581-015-2245.

What is the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE)?

By law, children with disabilities must be educated in the Least Restrictive Environment. Congress has defined the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) as the placement closest to a regular education environment yet still capable of meeting the needs of a particular child with disabilities. This means that the LRE varies according to those needs. A child must be educated in the regular classroom with supplemental aids and services unless he or she cannot be satisfactorily educated there.

EXAMPLES OF SUPPLEMENTAL AIDS AND SERVICES

Adaptations to classroom materials.

Special materials or equipment, including assistive technology (AT).

An individual instructional assistant.

When deciding a child’s placement, the school district must consider potential harmful and positive effects on the child. The district must also consider the quality and quantity of services the child needs. In addition, the educational impact on other students in the class must be considered. For example, a regular classroom may not be appropriate even with aids and services, if the child is greatly agitated by the noise and movement of a large group or is so disruptive that other students are unable to learn.

When a child is removed from a regular classroom, the school district must ensure that, whenever appropriate, the child will be with children who are in regular classes for nonacademic and extracurricular activities.

Unless the IEP requires another arrangement, children must be educated in the school they would attend if they didn’t have disabilities. If the IEP requires a different placement, the location of the placement must be as close as possible to the child’s home. 20 U.S.C. § 1412(a)(5), 34 C.F.R. § 300.114, OAR 581-015-2240 and 581-015-2250.

What if I don’t like the placement?

Any change in placement must be based on your child’s IEP goals. Placement decisions must be reviewed each time the IEP is significantly revised. Since an IEP must be reviewed annually, placement decisions also must be made at least annually. However, as a parent, you have the right to request a change in placement if you feel a placement is not working. The placement team, which includes you, then meets to discuss and decide placement.

Can I visit my child’s classroom?

Prior to making a placement decision, school districts should give you the opportunity to visit the proposed placement setting so you can determine whether that setting would be appropriate for your child. Once the placement decision has been made, you should still be able to visit the classroom. School districts may have policies about school visitation by parents and guests that are designed to eliminate distractions to both students and staff. So long as those policies are reasonable and applied equally to all, they are legitimate.

For instance, such policies might reasonably limit the amount of time of your visit, and the cumulative amount of visitation time per week or month. However, policies that do not allow you or your guests to take notes, or that limit your visitation time to a particularly small amount of time, are probably not reasonable.

What if I want the school district to pay for private school?

You always have the right to place your child in a private school at your own expense. In some cases, you may be entitled to reimbursement for private school costs from the school district if there is strong evidence that the district did not provide a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) to your child. However, before seeking reimbursement, you must give notice to the district of your intent to place your child privately and the reasons for this decision. This notice must be given at an IEP meeting or in writing within 10 business days (including holidays) before you remove your child from public school.

Once you give notice of your intention, the district may ask to evaluate your child or agree to change the IEP to address your concerns.

Reimbursement may be reduced or denied for any of the following reasons:

You did not give notice of your intent to place your child in private school.

The school district is providing FAPE to your child.

You did not make your child available for evaluations when asked by the district.

The private school does not provide FAPE.

20 U.S.C. § 1412(a)(10)(C), 34 C.F.R. § 300.148, OAR 581-015-2515.

See “Model Letter #3: Notice to school district regarding private school”

What are my placement rights?

You have the right as a member of the placement team to participate in discussions and decisions regarding placement. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(e); 34 C.F.R. § 300.116, OAR 581-015-2250.

You have the right to give or withhold consent for your child’s first placement in special education. If you do not consent, the school district may no longer utilize due process hearing procedures to override your refusal to consent. School districts do not have a legal obligation to provide FAPE to students with disabilities if the parent refuses consent for special education or revokes consent in writing for special education services. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(a)(1)(D)(i)(II), 34 C.F.R. § 300.300(b), OAR 581-015-2090(2), (4).

You have the right to receive prior written notice any time the district proposes a change in placement. You also have the right to written notice any time the district refuses your request to change your child’s placement. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(b)(3), 34 C.F.R. § 300.503(a), OAR 581-015-2310(1). See “Chapter 11: Notice Rules”

You have the right to request an IEP meeting, mediation, write a letter of complaint, or request a due process hearing to resolve any disagreement about placement. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(b), (e), (f), 34 C.F.R. § 300.151-300.153 and 300.506-300.518, OAR 581-015-2030 and 581- 015-2335 through 581-015-2385. See “Chapter 13: Resolving Disagreements”

Chapter 7: Extended School Year (ESY) Services

What is ESY?

Some children in special education programs need education services continued during the summer months or other vacations when school is not in session in order to maintain the skills they have learned as identified on the IEP goals. This includes related services and assistive technology.

ESY services must be provided when:

Your child is eligible for special education services.

Your child would regress considerably in identified areas of the IEP without an extended school year program.

Your child would require a substantial amount of time, after school starts, to recoup losses in identified goals of the IEP due to an extended school break.

34 C.F.R. § 300.106, OAR 581-015-2065.

How do I get ESY for my child?

Planning for an extended school year must begin at least several months before the vacation period starts. School districts take data about the child’s progress on an ongoing basis. This data can be used to determine a child’s regression and recoupment after break periods.

If you believe that your child may need ESY and it is not already part of the IEP, you should request that data be kept on your child’s regression and recoupment before and after the winter and spring breaks. Then request an IEP meeting to review the data and decide if your child is eligible for ESY. Often the meeting to decide ESY is held in the spring. Because the ESY decision is made by the IEP team, all of your IEP meeting rights apply. The decision to provide ESY must be written into your child’s IEP. If the school disagrees with giving your child ESY, the school must provide you with written notice of its decision.

You can supplement the school’s data by providing observations and documentation from summer months, especially if your child is getting no services. Collect notes and reports from teachers, specialists, and others at the end of one school year and the beginning of the next school year. This can also be done before and after other extended breaks. Documentation can include recommendations from private therapists or professionals who work with your child. These notes should describe your child’s behavior or skills at both points in time.

What if there is no data?

In the case of some children, there will be no data to show either the presence or absence of regression during breaks. In such cases, your child is still entitled to ESY services if the IEP team reasonably believes that there would be significant regression and recoupment problems.

What if I disagree with the ESY decision?

You may request mediation, write a letter of complaint, or request a due process hearing to resolve any disagreement about ESY. See “Chapter 13: Resolving Disagreements”

Where does my child go for ESY?

The school district does not have to provide a full range of placement options for ESY programs. Still, the district must offer placements that are appropriate to carry out those portions of your child’s goals on the IEP where problems with regression and recoupment were noted.

For example, an ESY placement might be a summer camp, a park and recreation program, or other non-classroom activity if your child’s primary need for ESY relates to socialization skills. For students who require maintenance of physical therapy goals, the placement may be at the student’s home.

Is summer school the same as ESY?

Summer school – which is not free – cannot take the place of ESY services. If ESY services are part of your child’s FAPE, they must be provided at no cost to you.

If a school district offers summer school to general education students, students with disabilities also must be given the opportunity to attend. Reasonable accommodations must be provided to students with disabilities.

Chapter 8: Physical Restraint and Seclusion

State regulations effective July 1, 2012 promote school safety by requiring planning, training, and parental involvement to regulate use of physical restraint and seclusion in schools.

What is physical restraint?

Oregon Administrative Rule (OAR) 581-021-0062(1)(a) defines physical restraint as “the restriction of a student’s movement by one or more persons holding the student or providing physical pressure upon the student.” The rule notes that physical restraint is not touching or holding a student without the use of force to direct the student or to assist the student in completing a task.

What is seclusion?

OAR 581-021-0062(1)(b) defines seclusion as “the involuntary confinement of a student alone in a room from which the student is physically prevented from leaving.”

Can the school use restraint or seclusion to make my child obey staff?

No. Physical restraint and seclusion may not be used for discipline, punishment or for the convenience of staff under the new law.

How long may restraint or seclusion last?

Only as long as your child poses a threat of imminent, serious physical harm to self or others. As soon as the threat of harm is over, your child must be released from the restraint or seclusion.

Your child should not be restrained or secluded for extended periods of time. Restraints and seclusions are emergency interventions that should not be used to manage behavior on a regular basis.

If your child is experiencing restraint or seclusion for long periods or if it is happening frequently, your child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) team should meet and look at changes to your child’s IEP, placement, and behavior plan.

What happens if my child is restrained or secluded for a long period of time?

New protections have been put into place for restraints and seclusions that last more that 30 minutes.

Your child must be allowed access to the bathroom and water.

Staff must get written authorization from a district administrator for the restraint/ seclusion to continue, including documenting the reason the restraint/seclusion needs to continue.

Staff must try to immediately contact you either by phone or e-mail to notify you of the length of the restraint or seclusion.

Are staff trained in how to safely engage in or avoid restraint and seclusion?

The law requires that any staff members who use physical restraint and seclusion on students are trained by a state-approved training program, unless the restraint or seclusion was required during an unforeseeable emergency situation.

If restraint or seclusion are used by staff who were not trained in a proper and approved technique, the district must notify you and explain why it was necessary to have an untrained staff member use restraint or seclusion. Staff training must include positive behavior support, conflict prevention, and de-escalation and crisis response techniques.

What happens after my child is restrained or secluded?

First, the school is required to notify you verbally or electronically by the end of the day the incident occurred. Within 24 hours of the incident, the district must provide you with written documentation including, at minimum:

Who implemented the restraint or seclusion;

How long the restraint or seclusion lasted;

Where it happened;

What was happening before it started;

How staff tried to de-escalate the situation; and

A description of what your child was doing that posed a reasonable threat of imminent bodily injury.

Within two days of the incident, staff must hold a debriefing meeting to discuss the incident. The purpose of this meeting is to look at why the incident happened and to take any action necessary to reduce the chances of it happening again.

You must be given notice of when that meeting will occur and you have the right to attend the meeting. However, because debriefing meetings must be held within two days, the district does not have to accommodate your schedule when setting a meeting time.

What is mechanical restraint?

Mechanical restraint is any device that is used to restrict your child’s movement; for example, strapping your child to a chair to prevent him/her from leaving the room. The district cannot mechanically restrain your child. Protective or stabilizing devices ordered by your child’s physician and vehicle safety restraints used during transport are not mechanical restraints.

What is prone restraint?

Prone restraint is a restraint in which a student is held face down on the floor. Prone restraint is not permitted under Oregon law.

Are there tools available to help reduce or stop my child’s difficult behaviors?

Your child’s disability may cause behaviors that interfere with learning or lead to disciplinary problems. There are two basic tools to help reduce or stop difficult behaviors: a functional behavior analysis (FBA) and a behavior plan (often called a BSP or BIP).

What is a functional behavior assessment (FBA)?

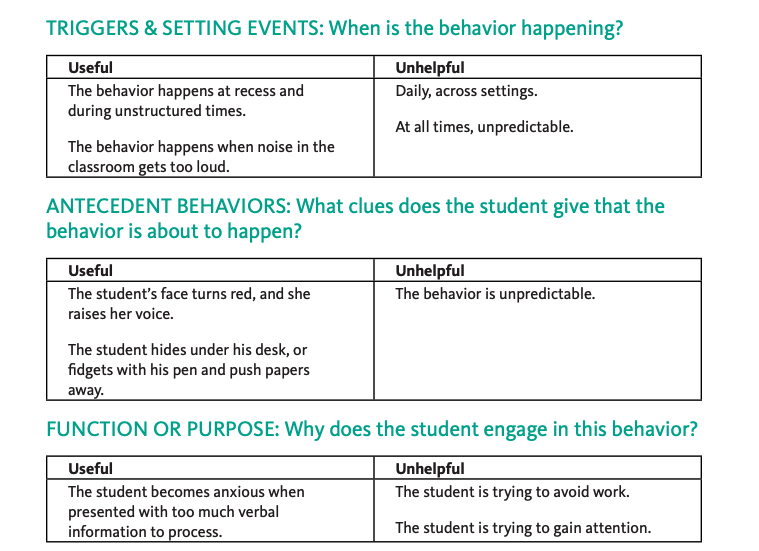

An FBA tries to answer three questions:

Why is the behavior happening? Identify triggers and setting events.

What clues does your child give that the behavior is about to happen? These clues are also called antecedent behaviors. It is very rare for a student to not give any signs that the situation is escalating.

Why does your child engage in this behavior? Figure out the function or purpose of the behavior. If your child seems to be seeking attention, ask why. Is the work too difficult? Does your child feel anxious that she won’t understand the work so that she wants an adult nearby?

Once these questions have been answered, a strategy is developed to deal with the behavior. A good FBA should describe your child in a way that makes sense to you.

When should an FBA be done?

An FBA should be done when:

Behavior consistently or predictably impacts your child’s learning, or the learning of your child’s classmates;

Your child has multiple suspensions or disciplinary referrals;

Your child is experiencing restraint or seclusion at school; or

Before a behavior plan is written. See “What is a behavior plan?”

What happens during an FBA?

The FBA starts with a school staff member (possibly a special education teacher, or a behavior specialist) observing your child in different settings, such as the playground and math class, on different days. That person writes down his/her observations. The IEP team then meets to review what was observed and members add their own observations and thoughts as to why the behavior might be happening. Parents are crucial to this process and have a right to be part of it. You know your child and have learned so much about when and why the behaviors happen. Share your expertise with the team during this process.

What does a good FBA look like?

To give you an idea of how useful an FBA can be when done thoughtfully, review the following examples.

What is a behavior plan?

A behavior plan (also called a BIP or BSP) is a set of instructions for the adults who work with your child. It is not a plan for what your child is required to do. The IEP team uses the information from the FBA to develop the behavior plan. A behavior plan should address the following:

1. What is the behavior theory or function of behavior that the team determined during the FBA? The plan should be based on that behavior theory or function.

Example: If the FBA behavioral theory or purpose is that your child becomes anxious when presented with too much verbal information to process, the plan should instruct adults to reduce their demands and verbal explanations when they see signs of trouble.

2. How can staff help eliminate or reduce the triggers and setting events?

Example: If loud noises are a trigger, can the student wear headphones? If transitions lead to behaviors, can the schedule be adjusted to make fewer transitions? Would a visual schedule help? If writing is a trigger, the plan should require adults to be flexible about how and when to ask your child to write.

3. Teach replacement behaviors. When you look at the function or purpose of the behaviors, is there another way for the student to get that need met? This part of the plan focuses on teaching the student new skills that will eventually replace the negative behaviors. (This could also be covered by a behavior goal in the IEP.)

Example: If your child becomes anxious when presented with too much verbal information to process, this part of the plan might encourage your child to learn to flip over a card or give a hand signal to indicate their anxiety level. This gives your child the opportunity to learn another way to communicate their needs to those around them.

4. How will staff respond when they see antecedent behaviors? The behavior plan should list what antecedent behaviors staff should look for, and specific ways they will respond when they see them.

Example: When the student raises his voice and his face gets red, staff will calmly suggest that he can take a walk or change activities, to give him space.

5. How will staff help the student de-escalate if the behaviors escalate? Even with the best behavior plan in place, there are times the behaviors will escalate. This part of the plan should focus on the best way to help the student de-escalate as quickly as possible.

Example: If your child is known to escalate when forced to admit a mistake, make sure that the behavior plan specifies that your child is not asked to apologize during de-escalation.

What should not be part of a behavior plan?

A behavior plan should not:

Be a behavior contract with a list of expectations for the student and consequences for not meeting those expectations.

Include half-day or reduced schedules unless you really feel these options are appropriate for your child.

Include negative consequences unless they have been shown to be effective and meaningful for your child.

What happens if the behavior plan does not work?

If your child’s behavior becomes worse or the plan does not result in significant reduction or elimination of the targeted behaviors within a month, you should ask the team to meet and discuss the problem.

The team should first consider whether the problem has been caused by poor implementation –meaning that staff has not followed it. If that is the problem, the team needs to provide better training or increased supports to ensure that the plan is followed.

On the other hand, if the plan has been properly followed without a good result, the team needs to look at revising the plan and the FBA behavior theory.

Chapter 9: School Discipline

Each school district in Oregon must publish and distribute a student conduct handbook. This handbook describes the school district’s expectations for student behavior, and lists behaviors that may result in exclusion from school. Some behaviors, such as not following school rules, can result in a short-term exclusion, called a suspension. More serious behaviors, such as bringing weapons or drugs to school, can result in a long-term exclusion, called an expulsion. State law does not allow the use of corporal punishment, such as spanking, paddling, or hitting children at school. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(k), 34 C.F.R. § 300.530- 300.536, OAR 581-015-2400 through 581-015-2425.

Can my child be suspended?

Students with disabilities may be suspended if they violate school rules. They can be disciplined to the same extent as children without disabilities. Repeated suspensions of a student with disabilities may suggest that a child is not receiving appropriate educational services.

You should request a review of your child’s IEP and behavior plan (or request a functional behavior assessment and behavior plan if one has not been developed) if your child is being disciplined repeatedly.

If your child is removed for more than 10 consecutive school days or is subjected to a series of removals that constitute a pattern, those removals are considered a change of placement. To determine if the removals from school create a pattern, school staff must answer a series of questions.

DETERMINING A PATTERN

Is your child’s behavior very similar to what caused earlier discipline?

For how long has your child been suspended each time?

How close together have the suspensions been?

If my child is suspended, what obligation does the district have to provide my child with educational services?

After 10 school days of suspension (whether or not it is a pattern) the school must provide services that allow your child to make progress toward IEP goals and have access to the regular education curriculum.

Can students with disabilities be expelled?

A school district cannot expel a student with a disability for misconduct that is a manifestation of the student’s disability. When a district decides to suspend or expel a student with a disability for more than 10 days, it must hold an IEP meeting within 10 days to determine whether the misconduct was related to the student’s disability. This is known as a manifestation determination.

The team must make specific factual findings before it may determine that the student’s behavior was not disability related. If the team determines that the conduct was not disability related, it may seek to expel the child as it would any other student.

Under these circumstances, you must be given notice of the IEP meeting and manifestation determination within a reasonable time before the meeting. You must also be given notice of the intended disciplinary action on the date that the decision to take disciplinary action is made. Finally, you must be given notice of procedural safeguards, which is an explanation of your rights under IDEA 2004.

Even if your child is expelled following a decision that the misconduct was not related to a disability, the school district must still provide services to your child in an interim alternative setting. The setting is determined by the IEP team and must allow your child to make progress toward IEP goals and continue to participate in the general school curriculum.

What is a manifestation determination?

The manifestation determination team decides if your child’s misconduct is related to a disability. The team must consider all relevant information, including evaluations, your own observations, your child’s IEP and placement (including behavior plans), related services, and other supports. The team must determine if:

Your child’s behavior was caused by, or had a direct and substantial relationship to, his or her disability; or

The conduct in question was a direct result of the school district’s failure to implement the IEP.

If the answer to either of these questions is yes, then your child cannot be expelled or disciplined for the behavior.

What if I disagree with the manifestation determination?

You may request an expedited due process hearing to challenge a manifestation determination or a change of placement arising from misconduct. Under these circumstances, your child is placed in the interim alternative placement during the due process hearing until the decision of the Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) is final, or until the end of the disciplinary removal, whichever occurs first, unless you and the district agree otherwise.

Who should be part of my child’s manifestation determination team?

A representative of the school district, you and all relevant members of the IEP team should be included. Together, you and the district determine the relevant members. If there are teachers or counselors at the school who understand your child and your child’s behavior, you can ask specifically for those staff members to be part of the manifestation determination team.

If there are professionals such as a private therapist working with your child outside of school they may have important input to contribute. It would be your responsibility to write to them in order that they are included on the team.

What is the school district’s obligation to review my child’s IEP after my child is disciplined?

After a manifestation determination has been completed, regardless of the outcome, the district must conduct a functional behavior assessment (FBA). The IEP team then uses the information gathered from the FBA to develop a behavior plan. If your child already had an FBA and a behavior plan before being disciplined, then the district must review and change them as necessary to address the behavior.

If the team found that the school did not implement your child’s IEP, then the school must immediately make changes to address the failures. You are always entitled to request a review of your child’s IEP and behavior plan. After a disciplinary issue arises, we recommend that you call an IEP meeting and have the team consider whether additional steps would help your child maintain proper behavior.

POSSIBLE STEPS TO MAINTAIN PROPER BEHAVIOR

Adding a more structured behavior intervention program to your child’s IEP.

Adding a related service, such as counseling or an instructional assistant.

Adding goals and objectives to help teach your child appropriate social and emotional responses or other skills needed for getting along in a school setting.

Increasing the amount of time in a special education program.

Changing your child’s special education placement to a different, possibly more restrictive, setting, such as a self-contained classroom, special school, alternative eschool, or residential program.

Reconsidering the behavioral theory that has been used to create the current behavior plan.

Below is an example of an IEP with goals and objectives designed to help teach appropriate social and emotional responses and skills:

Mary enjoys spending time with her peers, but does not manage peer conflicts successfully. Mary frequently exhibits inappropriate verbal behaviors like name calling and teasing and has engaged in physically harmful behavior such as pushing and biting on three occasions during the past month.

Mary will learn to use alternate strategies of conflict management in 80% of her peer conflicts.

In a structured role play, such as in social skills group, Mary will identify five situations that lead to conflicts with peers.

Mary will identify five behaviors and/or phrases that are appropriate in conflictsituations, such as walking away, taking five breaths, or telling the peer/ teacher whenshe is getting angry.

Mary will use her appropriate behaviors and/or phrases during periods of frustration oranger 80% of the time, with prompting.

Mary will use her appropriate behaviors and/or phrases during periods of frustration oranger 80% of the time, independently.

What if a child with a disability brings drugs or weapons to school?

If a student with a disability knowingly carries a weapon to school or to a school function, or knowingly uses, sells, or solicits the sale of illegal drugs at school or a school function, the school district may place the student in an appropriate interim alternative educational placement for up to 45 days. This placement is considered a safer temporary setting while the student’s appropriate educational placement is being worked out by the parent and district.

The district should conduct or review the functional behavior assessment and behavior plan for the student and make changes to address the behavior so it does not recur.

A parent who disagrees with an interim placement arising from the student’s involvement with a weapon or drugs may request an expedited due process hearing.

What if my child physically harms others or him/herself?

When Congress amended IDEA in 2004, it divided physical harm into three categories, and the district must respond to these categories differently.

SERIOUS BODILY INJURY

An injury likely to cause death or serious disfigurement. If your child causes this, theschool can immediately place him or her into an interim alternative placement.

INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR

Behavior likely to cause injury to your child or others. If your child’s behavior falls inthis category, the district must request an expedited due process hearing if they wish toplace your child into an interim alternative placement.

OTHER HARM

Behavior that would lead to the normal discipline process – up to 10 days suspensionor a manifestation determination if longer than 10 days.

Will my child get special education in the alternative placement?

The IEP team must determine what the interim alternative setting will be. The setting chosen by the team must allow your child to progress in the regular education curriculum (although in another setting) and make progress toward IEP goals.

What happens after the 45 days is over?

After the 45-day interim placement is over, your child must be returned to his or her current placement (the placement before the interim alternative setting), unless you and the district agree otherwise. However, if the district believes that it is dangerous for your child to return to the current placement while due process proceedings are ongoing, it may request an expedited hearing on this issue.

What if a student has not yet been found eligible for special education?

If the district knows that a student in regular education has a disability, the student cannot be excluded without following IDEA 2004 procedures. The district is considered to know that the student has a disability if:

The parent expressed concern in writing that the student needed special education.

The parent requested a special education evaluation.

A teacher or other staff expressed concern to the special education director or other supervisor about the behavior or performance of the child.

Even if a district cannot be deemed to have known that the student had a disability, the parent of a regular education student whom the district seeks to exclude may request an expedited evaluation. During the course of the evaluation, the student must remain in the placement determined by the district. 20 U.S.C. § 1415(k)(5), 34 C.F.R. § 300.534, OAR 581- 015-2440.

Chapter 10: Transition from Special Education to Adult Services

What are transition services?

Eligible students are entitled to special education services until the end of the year during which they turn 21 years of age. The transition from educational services to adult services can often be confusing. Transition services are designed to help the student move from school to employment, further education, adult services, independent living, or other types of community participation. These activities must be based on the student’s strengths, preferences, and interests. 20 U.S.C. § 1401(34), 34 C.F.R. § 300.43, OAR 581-015-2000(38).

When do transition services begin?

Under IDEA 2004, transition services must be included in the IEP that will be in effect when a student reaches age 16. Transition services can begin when the student is younger if the IEP team agrees that it is appropriate. 20 U.S.C. § 1414(d)(1)(A)(i)(VIII), 34 C.F.R. § 300.320(b), OAR 581-015-2200(2).

Who decides what transition services my child will get?

Transition services are decided at the IEP meeting. Besides the usual IEP team members, the school district should invite representatives from other public agencies who are likely to be responsible for providing or paying for transition services. Your child, whose preferences and participation are key transition factors, will also be invited. Because transition services are decided by the IEP team, all of your IEP rights apply. See “What are my IEP rights?”

What are examples of transition services?

In considering the activities to include in a transition plan, it is helpful for parents to first discuss their child’s desires for vocational, educational, independent living, and other goals for the future.

EXAMPLES OF TRANSITION SERVICES

Instruction

Community experiences

Employment development

Vocational evaluation